Today was a lovely fall day. While the sky was clouded over, the sun did peek out every now and then, its diffuse winter-ish light a testament to our planet’s progress on its journey to the “far side” of the sun. The temperature was cool, but after feeding the pigs and chickens and moving the chicken tractor I soon tossed off my knit wool cap and vest. With those chores out of the way I was ready to tackle my fall gardening project. Today was the day I planned to get my garden in shape for winter, with a look ahead to spring.

Last year I just about broke my back digging raised beds out of our hard, rocky soil. I’d planned to green manure the beds but an early snowfall killed the small-seeded fava beans before they got a chance to germinate. I also hadn’t gotten my fence finished, so the various animals that parade through our field managed to compress the soil somewhat over winter. By spring I had sunken beds that needed intense chopping and hoeing to become suitable for planting. Despite these failures we did get some early salad greens and we’re still enjoying tomatoes, although I’m unsure how much longer they’ll be ripening. But some stuff just didn’t grow well, and the problem was shallow soil that was low in nutrients and organic matter. So my goal this time around is to build up the soil over winter so that I get deeper soil, beds that are actually higher than ground level, and a higher nutrient content in the soil. Sure, I could just go buy a truckload of topsoil, but I didn’t want to go that route. We don’t own a pickup truck, it’s expensive to buy topsoil, and I wouldn’t really know where the stuff had come from. I wanted to do it myself.

I had two strategies under consideration, and I ended up trying both of them today. First up was the Lasagna Garden. This is a way to build up a plantable garden over winter. Basically, you lay some kind of paper product (newspaper, cardboard, etc) on the ground in the shape of your garden-to-be. Then you make a “lasagna” by layering compostable materials, alternating between “green” (e.g. grass clippings, kitchen scraps) and “brown” (e.g. straw, hay, dried leaves) layers. The stuff rots down over winter to become humus-rich soil full of organic matter and perfect for spring planting.

I started with the layer of paper products, in our case feed bags. I’d been saving these up and had a rather tall stack of them. They are made of two layers of heavy-duty paper, sewn shut with string, and contain only a small amount of glue along the bottom and top seams between the two layers. I decided not to be a purist; I don’t think the amount of glue is enough to contaminate my garden. And as I didn’t have enough cardboard or any newspaper around it seemed the smartest way to make use of something that would otherwise be tossed into the recycling box. I already had the outline of a bed – it was one I’d dug last year and didn’t use this year, so it was weedy and hard. A good candidate, I thought, for this “no-dig” garden method.

After bringing the pile of feed bags to the garden, I brought out my brand-new wheelbarrow (yikes, are these things expensive! but being the procrastinator I am, I simply didn’t have time to shop around for a used one; at least I know I’ll get lots of use out of it). I headed to the compost pile and rolled back the logs barring the bottom front, and took a good look at what I had. I’d started this pile over a year ago but I don’t seem to have much luck with compost. My first attempt at our last house resulted in a soppy, wet, yucky mess littered with eggshells. I hadn’t included enough brown matter. This time I seem to have erred in the other direction. I added straw whenever I dumped a bucket of kitchen scraps on the pile, and now I had a whole lot of brown matter but nothing that looked like soil. Still, I could clearly see some rotting food scraps in there.

To make matters more complicated, I’d dumped lots of weeds from the garden on the pile last month and I’m quite sure many of them were in seed. This is a no-no when using compost to build a garden bed. But I decided it would be much easier to just weed a lot next spring than to try and separate the stuff now (probably impossible, anyway). Not one to be easily deterred I filled up my wheelbarrow and began piling it on top of the feed bags. It wasn’t really a lasagna, since I only had two layers. But since my compost seemed to be a mixture of brown and green (okay, more brown but still…) I decided to just lay it on the paper and hope for the best.

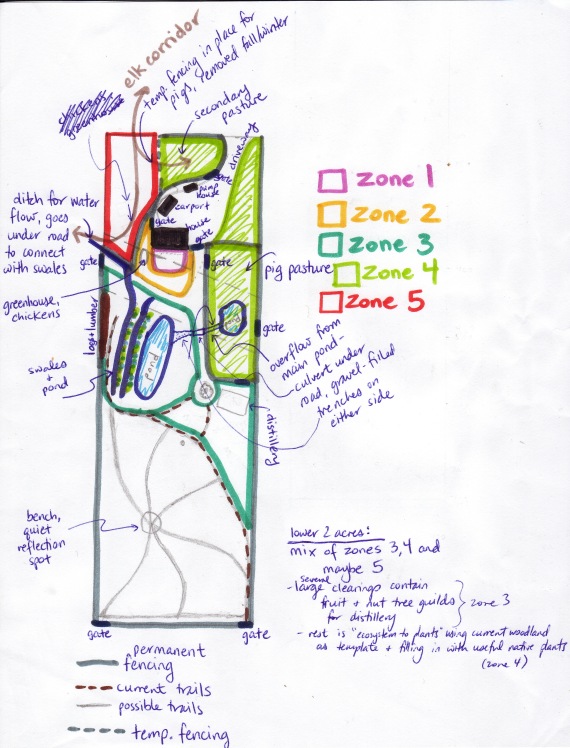

When I was done I realized that I was still missing an ingredient from the usual lasagna recipes: soil. I wasn’t sure how important this was, and looking around me I wondered where I would get soil from. Our field is so thickly planted with grass that you can’t put a shovel into it, and I didn’t want to tear up part of the field anyway. What lies around the edges isn’t thickly grown because the soil there is pretty crappy stuff and I couldn’t see how adding dusty, rocky, lifeless “soil” was going to help me build a garden bed. I knew the soil underneath my feed bags was in bad shape, so adding a top layer of soil would probably be a good thing. But I wasn’t about to go buy some. As I stared off into the distance I thought how silly it was to live on 4 acres and not have a ready source of soil, and then the answer hit me. I was staring at our woods! The ground in there is lovely humus, rich with leaves and bugs. If I scraped some of it off the walking paths I wouldn’t be depriving the forest itself of much, and I’d be clearing up some trails at the same time. So with my wheelbarrow and shovel I headed into our woods.

It was lovely work. The dirt smelled wonderful, and it came up with a nice layer of rotting leaves. It had the perfect texture and “tilth”, and I laughed to myself that I had discovered the perfect source of soil right here in our own woods – free for the taking! I only needed two wheelbarrows full (about 12 cu ft total) to cover up my garden bed. But that was enough for my back muscles anyways. And I got this in just one small patch of pathway. Not only did I solve today’s problem, but now I know I’ve got a wonderful source of humus for topping up beds when I plant next spring.

The finished bed looked pretty good, I thought:

Though I won’t be surprised if it breaks down so much that it’s not very high come spring. Still, it’s a start!

The other option I’d considered for building soil was trying the green manure thing again. Since I had used all my compost and feed bags on the one large bed, I decided I might as well try seeding the smaller beds. However, once again I improvised based on what I had on hand, not feeling like spending my Sunday-in-the-garden driving around to nurseries instead. I had a lot of small-seeded fava beans left over from last year, but they had been inoculated back then and sat in a plastic bag in the potting shed all year long. I figured it was a total crap shoot as to whether these things would germinate, but what the heck. Last year I’d sprinkled them on top of the soil, which I think was a mistake. This year I took the time to plant them in rows, gently covering them up with my hands. I used a pretty dense line of seeds assuming that I’d be lucky if half of them germinated. It was quick work and I enjoyed it very much.

And, just for the heck of it, I scattered some of them on top of my lasagna bed. It wouldn’t matter if they didn’t germinate, but if they did I’d have some extra organic matter to turn into it next spring before planting.

As I was doing this I discovered that my kale seemed to have come back to life in the last couple of weeks. I’d planted it in summer, really not the right time, and it looked small, sickly, and pale all that time. I’d given up on it when, to my surprise today, I discovered it had been revived by the cool wet weather. That was a nice bonus to an already lovely day of hard work. Looking forward to toasting up some kale chips soon!